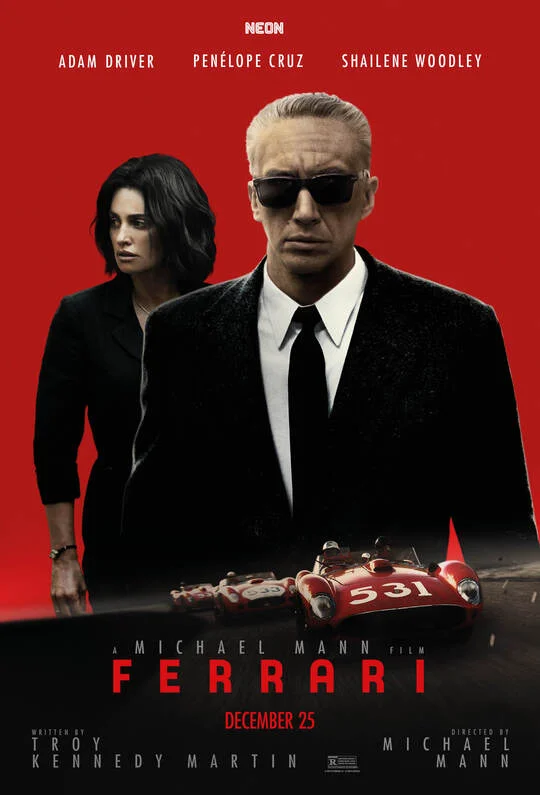

Ferrari 4K 2023 2160p WEB-DL

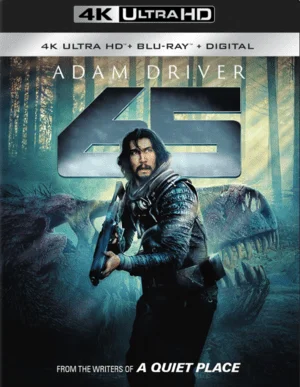

Cast: Adam Driver, Shailene Woodley, Giuseppe Festinese, Alessandro Cremona, Derek Hill, Leonardo Caimi, Penélope Cruz, Gabriel Leone, Michele Savoia, Jacopo Bruno, Domenico Fortunato, Damiano Neviani, Giuseppe Bonifati, Franca Abategiovanni, Marino Franchitti, Valentina Bellè, Luciano Miele, Daniela Piperno.

A biopic about the legendary designer and racing driver Enzo Ferrari. In the summer of 1957, he decides to take part in the 1000-mile Mille Miglia circuit, risking absolutely everything.

Ferrari 4K Review

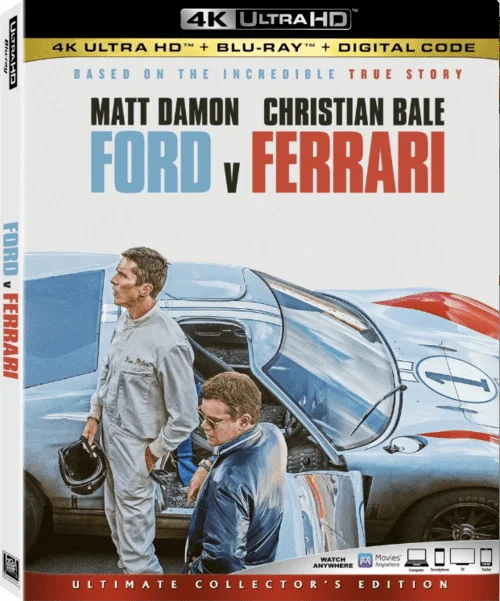

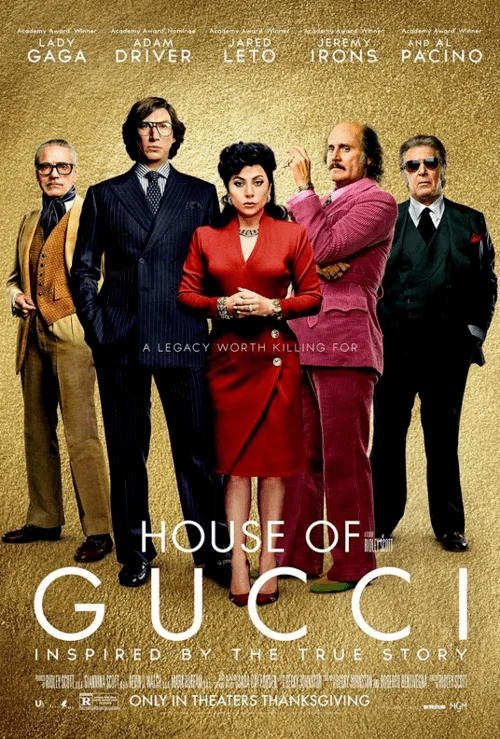

The first day of the Italian Mostra was rather quiet and calm: Edoardo De Angelis's programmatic "Comandante" and Pablo Larraín's funny but not hilarious "The Count" did not bring any revelations to the audience. But on August 31, the competition screenings began to buzz from the very morning with cross screenings of Luc Besson's "Dogman" and Michael Mann's "Ferrari". If the appearance of the Frenchman in the main program were treated with curiosity, but distrust, the picture of Enzo in advance gained credits of trust, supported by promotional materials: another Italian suit sat on Adam Driver as fit (still not cooled the memory of "House of Gucci" Ridley Scott). Yes, and the racers in the case, the audience saw recently in "Ford vs. Ferrari": the Italians in the tape James Mangolda were presented stereotypically funny - it's time for opponents to speak for themselves.

"Ferrari" though it begins with black-and-white terry shots of (what appears to be) a newsreel with Enzo still at the wheel, it still doesn't seek to embrace the vastness by painting the GI Bill chapter by chapter, instead focusing on the late 1950s. Commendatore Enzo is desperately trying to keep up with three families at once, methodically maneuvering between wife Laura (Penelope Cruz), overcome with grief after the death of their son Dino, mistress Linda (Shailene Woodley) with her illegitimate boy Piero, and Scuderia, the main love of the design engineer's life. Despite the limited scope of the chronology and the thoughtfully chosen running time, it can't be said that great director Michael Mann experiments with narrative or departs from the dramatic sketches adopted in the genre of biographies of the greats. The script is based on a literary portrait of Enzo by Brock Yates, and on screen, the picture is intoxicatingly old-fashioned: classic, like those very Italian costumes, perfectly cut and well fitted.

Audience perception will vary considerably depending on immersion in the history of Formula One, Le Mans, Mille Miglia and other significant races, passion for racing in general and other input: in any case, attempting to study Enzo and Scuderia biography right before the screening may deprive Mann of the second trump card up his sleeve. The first one, Adam Driver, of course, cannot be taken away: the American actor copes grandly with the promotion of Italian brands by cinematic means, and Michael Mann closely follows Enzo's monumental article, expressive gait and delineated gestures. Ferrari does not speak much, and if he opens his mouth, he rushes with aphorisms, more often he looks thoughtfully, calculating the risks and conditions that will certainly have to be taken. The camera now and then clings to the neck and shoulders of a textured man - the bend of any nature he is ready to bear.

Despite its craving for antique sculpture, "Ferrari" is devoid of excessive seriousness, dialogues with eternity and does not economize on sentiment - humor and guilt. The movie is mostly English-language, but Mann is firmly enchanted by the Italian nature and, like a Catholic priest, marries bitterness and joy. For both, the wife Ferrari, played by Penelope Cruz, is responsible - a woman betrothed not to the eternally absent Enzo, but to her own sadness: every appearance of Laura in the frame is heartbreaking, or makes you laugh at the fearless attacks on the world of men. Signora Ferrari was her husband's business partner and money manager: Penelope Cruz, with venomous fatigue and ironic desperation, shakes the air now and then with bullshit screams, volleys of gunfire and nervous breakdowns in which Cruz is not and will not be equaled. Shailene Woodley was much less lucky - except for the role of a waiting woman in a quiet cove, the script could not offer the artist anything.

Enzo wanders in a circle of affections, unable to stop, and Mann's movie could go on endlessly, but in the last third of the genre comes into play: to solve the financial problems of Scuderia can win a major race, soon on Mille Miglia will announce the start. But "Ferrari" is in no hurry to get on the rails of movies about the rehearsal of success and triumph afterwards, giving the third act to the climactic competition: the steepest turns of Enzo are waiting outside the track, with the roadbed racers meet the racers.

Mann's measured pacing relies on classic (retro?) masculinity, of the sort extolled in Robert Redford's pictures. Mann's parallel montage rhymes communion in church and a test run on the track, switching from a crucified Jesus to the metal circle of a stopwatch. If cars are the main religion in the house of Ferrari, Enzo is a god, or at least an ancient demigod in a jacket. A poetic ballad about Hephaestus or a continuation of the era of brands on the movie theater Olympus? Who knows.

Ferrari 4K Review

The first day of the Italian Mostra was rather quiet and calm: Edoardo De Angelis's programmatic "Comandante" and Pablo Larraín's funny but not hilarious "The Count" did not bring any revelations to the audience. But on August 31, the competition screenings began to buzz from the very morning with cross screenings of Luc Besson's "Dogman" and Michael Mann's "Ferrari". If the appearance of the Frenchman in the main program were treated with curiosity, but distrust, the picture of Enzo in advance gained credits of trust, supported by promotional materials: another Italian suit sat on Adam Driver as fit (still not cooled the memory of "House of Gucci" Ridley Scott). Yes, and the racers in the case, the audience saw recently in "Ford vs. Ferrari": the Italians in the tape James Mangolda were presented stereotypically funny - it's time for opponents to speak for themselves.

"Ferrari" though it begins with black-and-white terry shots of (what appears to be) a newsreel with Enzo still at the wheel, it still doesn't seek to embrace the vastness by painting the GI Bill chapter by chapter, instead focusing on the late 1950s. Commendatore Enzo is desperately trying to keep up with three families at once, methodically maneuvering between wife Laura (Penelope Cruz), overcome with grief after the death of their son Dino, mistress Linda (Shailene Woodley) with her illegitimate boy Piero, and Scuderia, the main love of the design engineer's life. Despite the limited scope of the chronology and the thoughtfully chosen running time, it can't be said that great director Michael Mann experiments with narrative or departs from the dramatic sketches adopted in the genre of biographies of the greats. The script is based on a literary portrait of Enzo by Brock Yates, and on screen, the picture is intoxicatingly old-fashioned: classic, like those very Italian costumes, perfectly cut and well fitted.

Audience perception will vary considerably depending on immersion in the history of Formula One, Le Mans, Mille Miglia and other significant races, passion for racing in general and other input: in any case, attempting to study Enzo and Scuderia biography right before the screening may deprive Mann of the second trump card up his sleeve. The first one, Adam Driver, of course, cannot be taken away: the American actor copes grandly with the promotion of Italian brands by cinematic means, and Michael Mann closely follows Enzo's monumental article, expressive gait and delineated gestures. Ferrari does not speak much, and if he opens his mouth, he rushes with aphorisms, more often he looks thoughtfully, calculating the risks and conditions that will certainly have to be taken. The camera now and then clings to the neck and shoulders of a textured man - the bend of any nature he is ready to bear.

Despite its craving for antique sculpture, "Ferrari" is devoid of excessive seriousness, dialogues with eternity and does not economize on sentiment - humor and guilt. The movie is mostly English-language, but Mann is firmly enchanted by the Italian nature and, like a Catholic priest, marries bitterness and joy. For both, the wife Ferrari, played by Penelope Cruz, is responsible - a woman betrothed not to the eternally absent Enzo, but to her own sadness: every appearance of Laura in the frame is heartbreaking, or makes you laugh at the fearless attacks on the world of men. Signora Ferrari was her husband's business partner and money manager: Penelope Cruz, with venomous fatigue and ironic desperation, shakes the air now and then with bullshit screams, volleys of gunfire and nervous breakdowns in which Cruz is not and will not be equaled. Shailene Woodley was much less lucky - except for the role of a waiting woman in a quiet cove, the script could not offer the artist anything.

Enzo wanders in a circle of affections, unable to stop, and Mann's movie could go on endlessly, but in the last third of the genre comes into play: to solve the financial problems of Scuderia can win a major race, soon on Mille Miglia will announce the start. But "Ferrari" is in no hurry to get on the rails of movies about the rehearsal of success and triumph afterwards, giving the third act to the climactic competition: the steepest turns of Enzo are waiting outside the track, with the roadbed racers meet the racers.

Mann's measured pacing relies on classic (retro?) masculinity, of the sort extolled in Robert Redford's pictures. Mann's parallel montage rhymes communion in church and a test run on the track, switching from a crucified Jesus to the metal circle of a stopwatch. If cars are the main religion in the house of Ferrari, Enzo is a god, or at least an ancient demigod in a jacket. A poetic ballad about Hephaestus or a continuation of the era of brands on the movie theater Olympus? Who knows.

File size: 13.9 GB

Trailer Ferrari 4K 2023 2160p WEB-DL

Latest added movies

Comments on the movie

Add a comment

like

like do not like

do not like