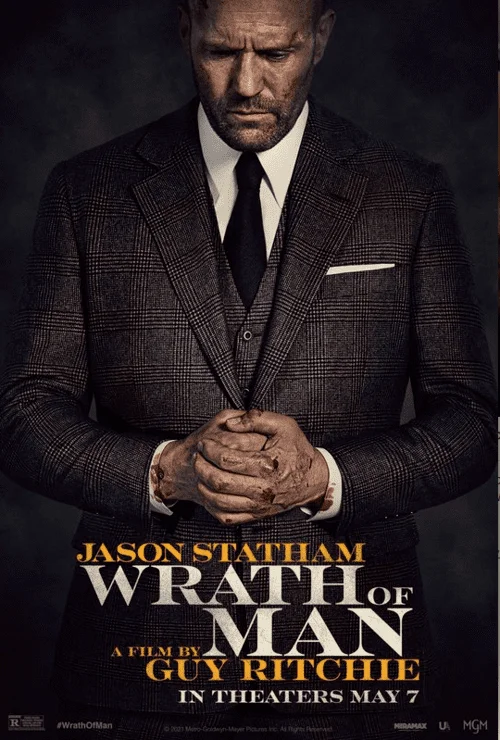

Wrath of Man 4K 2021 Ultra HD 2160p

Cast: Jason Statham, Holt McCallany, Josh Hartnett, Rocci Williams, Jeffrey Donovan, Scott Eastwood, Andy Garcia, Deobia Oparei, Laz Alonso, Raúl Castillo, Chris Reilly, Eddie Marsan, Niamh Algar, Tadhg Murphy, Alessandro Babalola, Mark Arnold, Gerald Tyler, Alex Ferns.

H (Jason Statham) is burning with a thirst for justice, despite his mysterious and cold appearance. He is pursuing personal motives and is going to find the customer of a series of multimillion-dollar robberies that stunned Los Angeles. In this incomprehensible and mysterious game, everyone has a role to play, but all the culprits will certainly know human anger.

Wrath of Man 4K Review

A smart bald man (Jason Statham, who else) comes for an interview at the collection service. He does not speak much, he does not turn his face to the future boss during the conversation, continuing to stubbornly stare at the wall while the boss mumbles somewhere behind. And when he does get to work, he proves once again that he is not destined to shine with his companionable abilities: at corporate parties, he constantly keeps silent and in the very first days manages to make enemies among his colleagues.

All collectors have callsigns - Sticky John, Machine Gun, - so our hero gets his nickname, H. You can't imagine any more boring thing, but the newly-made Eich himself, let's face it, is a person without any distinctive features. One thing is clear about him for sure: he's too cool for those greasy, out-of-print collectors who troll each other in locker rooms and wipe the chairs of working machines for days on end. Colleagues begin to suspect something when, during one of the attacks, which have become more frequent in recent months, H, in cold blood, almost with the endurance of a professional hitman, deals with the thieves. Now simple hard workers, and with them the audience, will have to find out who the hero of State is - a cat in a poke or a wolf in sheep's clothing. And if a wolf, then does he perform in the circus.

When a lion is hungry, he eats. When Guy Ritchie wants to make a kid's movie (almost always), he makes it. And this time not some daring ironic film about the life of retired criminals, but this, you know, a refined Statetem movie, where everyone speaks in hoarse, choked voices, where any cool phrase turns into a pretentious quote for a meme with a wolf, but the main character forbids himself to die until he takes revenge. After filming The Gentlemen, Richie seemed to have decided to take a break and spend the weekend with a short, but still a marathon of Craig S. Zahler films (Roll On Asphalt, Fight in Block 99). I spent it. I didn't understand everything, but I learned the main lesson: if irony from my films is replaced by cold cynicism, something metapazan can come out.

Therefore, it is very funny to perceive "Human Wrath" as a remake of the original French thriller "The Collector" (and he, no matter how difficult it is to believe it, is). After all, Nicolas Buchriff had a quiet drama about the boring everyday life of money carriers who smoke weed, talk about all sorts of nonsense, burn out at corporate parties, but cannot hide their inner scrapping, their fatigue from life and themselves. Gradually, this plot more and more concentrated on the strange newcomer Alexandra, and the viewer found out why he went to work in cash collection. An awkward outsider, he revealed his true nature and turned into a cold-blooded avenger before our eyes. Swap Dupontelle (let's say, not at all heroic in appearance) for Jason State - you get a completely different movie.

But Richie it - different that is - just right. He generally does not like to stand on ceremony with the canons: Holmes is not Holmes, King Arthur is a street thief, and only on "Aladdin" the rebellion against everything generally accepted seems to have stalled. To "break up" after a couple of films, turning almost a festival tragedy into a genre puzzle. Pretentious, of course, but pretentiously pretentious: again these expressive opening credits, again the nonlinear structure of the narrative, and even the pretentious division into acts, the funniest of which is the duplication of chapter titles by the heroes themselves (in "Scorched Earth" by H's six, for example, are outraged that they burned out the whole earth in search of the right people). Not a trace of the French film, but not so much of the old playful Richie either.

He uses fanciful visual techniques more diligently than usual: he will shoot the opening scene in one take, placing the camera in a collector's car, which is about to be robbed, then during a static dialogue he uses sharp camera departures. In other words, Richie is more interesting to play with the substance of the genre, to transform the reference state-of-the-art cinema, where the well-known actor again changes his profession (from a carrier and mechanic to a collector) at the level of form. The legacy is that Richie is the images of masculine bully men, in between work joking about dicks and sneering at each other, like eighth-graders bullers.

In this situation, when a self-ironic author, always holding himself somewhere above the genre, takes on a simple, like two-two, and incredibly serious story, there are two ways out. The first is to get something in the spirit of "Spy" with the same State. A thoroughly parody movie that turns hackneyed images of special agents into one big joke. The second is a postironic synthesis of these two forms, a concentrated genre fusion, which is so outrageously vulgar and serious (and, moreover, filmed aesthetically) that it already gives a certain pleasure. It turned out rather the second.

Perhaps this is all part of the Stockholm Syndrome. I really don't want to believe that Richie just took and shot a seasoned male action movie with the star of "Adrenaline" and the latest "Fast and the Furious". But in this equation there are too many strange elements that do not fit into the laws of logic for the answer to be so simple. State stubbornly communicates with kid quotes, because it is better to live one day as a wolf than a hundred years as a jackal, and kills enemies (mainly dealers in child porn and murderers, he is still a noble avenger), but Richie, as if realizing how much his hero absurd, just enjoying the texture of the story. Perhaps that is why in the second half Eich himself fades into the background and gives way to those whom he, in fact, is going to take revenge on - the war veterans abandoned by their homeland, robbing cash collection vehicles.

It's easier to imagine Human Wrath as a film about any episodic character of Guy Ritchie: let's say, Boris Razor (they have a lot in common with State, by the way - you can get into both of them). Imagining this character in the background, in the background of the story is as easy as shelling pears - usually such colorful, but the same type of characters fit perfectly into the hectic narrative, overflowing with images of thugs, mafiosi and, so to speak, ordinary people who are not lucky enough to find themselves between two fires. But only if you give Boris Razor a leading role and make him growl in broken English with pretentious phrases, along the way loading the whole story with biblical quotes, it will come out, as you can imagine, tiring. In Human Wrath, Richie clings not to the characters, as it was before, but to the very texture of the story - to a series of events that jump in chronology, sending the viewer from one point of the plot to another (look at how often the inscriptions flash on the screen: 3 months ago "," 2 weeks ago "," a long time ago in a distant galaxy "). Richie seems to have lost touch with his favorite characters, and with it the sense of dynamics, replaced by directorial graphomania. Instead of a movie - albeit spectacular, but still an exercise. Instead of some special look at the genre - a typical representative of it.

File size: 20.7 GB

Trailer Wrath of Man 4K 2021 Ultra HD 2160p

Latest added movies

Comments on the movie

Add a comment

like

like do not like

do not like