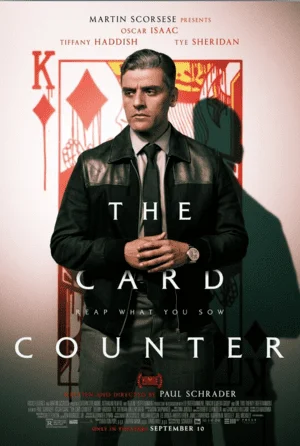

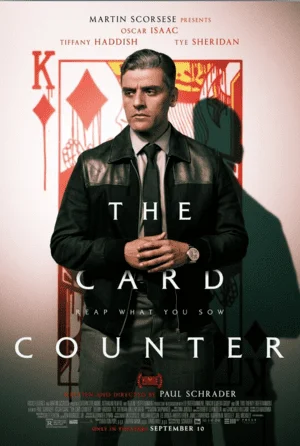

The Card Counter 4K 2021 2160p WEB-DL

Cast: Oscar Isaac, Tiffany Haddish, Tye Sheridan, Willem Dafoe, Alexander Babara, Bobby C. King, Ekaterina Baker, Bryan Truong, Dylan Flashner, Adrienne Lau, Joel Michaely, Rachel Michiko Whitney, Muhsin Fliah, Joseph Singletary, Kirill Sheynerman, Amia Edwards, Britton Webb, Amye Gousset.

Former military man William Tell has long been out of work and fell into gambling addiction. But one day Kirk comes to him, who persuades the colonel to take revenge on their former enemy. Tell disagrees and wants to change Kirk's mind as he walks around the Las Vegas casinos with him. However, the past still catches up with them.

The Card Counter 4K Review

William Tell (Oscar Isaac) is a professional card player who has mastered the art of deck handling and statistical card counting in blackjack. He does not like to stick his head out and slowly travels from state to state, where he beats provincial casinos for small sums so that there are no unnecessary problems with the administration. William learned to play so well in a military prison, where he thundered for 10 years for participating in the torture of prisoners in Abu Ghraib, while his boss, Major John Gordo (Willem Dafoe), remained at large. At one of the military conventions, where Tell comes to play cards, he just meets the former boss, as well as Kirk (Tai Sheridan), whose father was also an employee of Gordo. He offers William to kill the major, but the hero has completely different plans: he takes the boy with him on the road and through agent La Linda (Tiffany Hadish) subscribes to serious poker tournaments. Everything to make money, help Kirk and drive away stupid thoughts of stupid revenge from him.

Before checking into a motel room in another provincial town, the protagonist of "The Card Counter" performs the same ritual: she covers furniture with white cloth, turns the room into a sterile monotonous room. He is preoccupied with control and passionate about the everyday, used to doing everything in order and painting life every minute - as they did in prison, where Tell spent almost ten years. Apart from the details about the conclusion, all this is similar to how Paul Schroeder himself, the director of more than 20 films, better known to the general audience as the screenwriter of Scorsese's Taxi Driver and Raging Bull, can work. His new picture, echoing its (true, localized) name, is as if it itself was made with a The Card Counter: take it apart, and it turns out that we have already seen exactly the same film from exactly the same author. Not even once.

The protagonist is a military man crippled by the past (Travis Bickle from Taxi Driver served in Vietnam, the hero of Schroeder's previous film, The Shepherd's Diary, traveled to Iraq). He suffers from obvious psychological problems and always writes down his thoughts in a diary (Bickle, however, limited himself to offscreen speech). He has a love interest and, optionally, a minor protégé, whom he unexpectedly takes under his wing: Tye Sheridan in "The Card Counter" in this sense is a brother of the heroine Jodie Foster from the same "Taxi Driver". The whole story of Schroeder's heroes is a journey down the rabbit hole of an unstable psyche, which is at the same time connected with the current political agenda. "Taxi Driver" between the lines expressed dissatisfaction with the two-faced government, "The Shepherd's Diary" spoke openly about environmental problems, but "The Card Counter" returns to the problems of blind militarism and the brutality of the special services of the Bush junior era. Each character here is not just an individual broken-hearted person, but a metaphorical reflection of America of a particular era.

Schroeder could be rightly accused of self-copying, but for some reason I don't want to: it is clear that for him plots of the same root are not an end in themselves, but rather a convenient template with which the director likes to play, rearranging the figures and changing individual details in search of new meanings. You come up with a new profession for the hero, and now a whole untapped world opens up, in this case gambling, whose mechanics the film delves into so deeply that Steven Soderbergh himself would envy (there are, say, long explanations of the theory of probability in blackjack). You replace the war with a prison - and the hero acquires an even greater duality. He is not just a former soldier unable to adapt to a peaceful life. William Tell is a man who tortured people of his own free will and knows that he will never be able to forgive himself for it.

The Card Counter is heroic in the sense that Isaac's character dictates every narrative decision. The seemingly straightforward plot about revenge turns into fiction - after all, Tell knows that there is no one to take revenge: he himself happily tortured the prisoners. William finds his life purpose in "saving" Kirk, but he himself seems to understand that he is simply grasping at the illusory chance for redemption, which will not be and cannot be. And the film after him blurs the plot, distracts from the central conflict and devotes himself to routine: the next tournament, everyday conversation at the bar, conversation in the car, quiet observations of strange heroes that inhabit this world (like a Ukrainian player wearing clothes with an American flag and chanting "US-A" after each winning hand). He was filmed somehow especially casually: the general plan, the dialogue "eight", always direct angles, in general, strictly according to the training manual. Schroeder's style variety allows himself only in flashbacks from prison, where uncomfortable wide-angle optics suddenly appear, terribly distorting space and faces. Memory is beyond the control of control freak William.

Schroeder's cinema can even be called an "anti-thriller" - instead of going to aggravate the conflict, "The Card Counter" deliberately avoids it, until the last delay the moment when the shadow hanging over the hero finally makes itself felt. In contrast to Taxi Driver and Diary of a Shepherd, however, here this unwillingness to move towards the finale can also be read as the author's uncertainty. Schroeder usually did well at endings, but she's the weakest point in The Crew. The ending comes out of nowhere and goes, in general, to nowhere, to the only serious act of violence, from which the camera for some reason shyly hides behind the wall. Schroeder's anemicity has always been justified by a culminating surge of energy, but catharsis does not occur here: playing exactly the same cards as always, he suddenly stumbles at the very end. Apparently, the deck at the kiosk was tucked in.

File size: 11.7 GB

Trailer The Card Counter 4K 2021 2160p WEB-DL

Latest added movies

Comments on the movie

Add a comment

like

like do not like

do not like