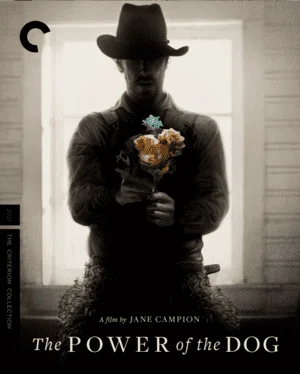

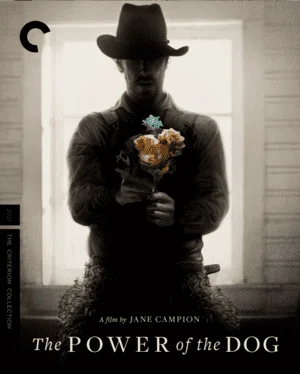

The Power of the Dog 4K 2021 Ultra HD 2160p

Cast: Benedict Cumberbatch, Kirsten Dunst, Jesse Plemons, Kodi Smit-McPhee, Geneviève Lemon, Kenneth Radley, Sean Keenan, George Mason, Ramontay McConnell, David Denis, Cohen Holloway, Max Mata, Josh Owen, Alistair Sewell, Eddie Campbell, Alice Englert, Bryony Skillington, Jacque Drew.

The film is based on the novel of the same name by Thomas Savage. 1925. A reserved and oppressive rancher in Missouri tries to separate his brother from the local widow, but instead finds unexpected love himself.

The Power of the Dog 4K Review

Montana, 1925. The Burbank brothers, Phil (Benedict Cumberbatch) and George (Jesse Plemons), own a small ranch and have lived together inseparably for 40 years. When George marries local widow Rose (Kirsten Dunst), lonely Phil decides to get revenge.

Phil Burbank can't stand weakness. More than 20 years after losing his close friend and mentor Bronco Henry, with whom he was bound not only by friendship but also by something more hidden and unspoken, he has become a hermit, not at all a devout monk, rarely washed and not about to return to civilization. Surrounded by loyal followers-helpers and a herd of cows, Phil is tough, principled, and equally unprincipled. His past unexpectedly lurks in his Latin and Greek studies at Yale--his career could have taken off in earnest--but instead Phil has settled far outside the city limits. Unlike his soft and compliant brother George, Phil wears his loneliness, masculinity, enclosed stink and stripped down skins proudly, like leather trousers ingeniously concealing his incompetence. Phil has secrets that he is not ready to admit to himself, much less to those around him.

Based on Thomas Savage's 1967 novel of the same name (and a forgotten classic of queer literature), Campion's film can be mistaken for a Western, give it the prefix "neo-" and safely interpret it as unambiguous or, at most, strictly binary. There is no shooting, no gangs, no nobility in the film, and all the fights are emotional and with destabilizing cranial pressure. The Oscar winner for "The Piano." 1993, another prominent explorer of isolation and literal dumbness in foreign lands, treats every American's familiar pastorals and their male inhabitants with a particular empathy and even mysticism.

The title refers to the biblical psalm, "Deliver my soul from the sword, and my heart from the power of the dog." Campion interrupts his decade-long vacation with a powerful surgical dissection of his notorious "toxic masculinity" with a blindly set-up for the "right man" and his supposed unawareness of his mental state. Phil's cracking up begins with the arrival not only of Rose, but also of her son Peter (Cody Smith-McPhee), a high school student and prospective student who has come to join his new family for the vacations. His outcast status is close to Phil's, though he initially refuses to admit it.

Peter plans to become a doctor: he cuts up and quietly wrings the necks of rabbits, cuts up half-dead cows, and likes to make paper flowers. Phil calls him a "softie," brought up by his nervous mother. But Peter, like him, also knows a plague of self-isolation, sometimes voluntary, sometimes forced. Suddenly the teenager begins to feel on equal footing with Phil, which makes the entire third act imbued with inescapable psychosexual tension. Rose is determined to prevent her son's friendship with Phil. Having long since lost her husband in a suicide and remarried to George, she gradually begins to fuel her fear with alcohol, worsening her condition.

In two hours Campion, who won the Silver Lion for directing at the Venice Festival, leisurely and with manic attention to detail stratifies the true nature of the main character, referring alternately to Terrence Malick's "Days of Harvest" with two lost lovers going on a crime spree; to the Coen Brothers' "Old Men Don't Belong Here" with the inevitability of fate's devilish footsteps, and to Claire Denis' "A Good Job" about the soldier's legion with the cultivation of violence and forever shattered destinies. Accompanying the director's references is piercing camerawork by Erie Wegner ("The True Story of the Kelly Gang"), capturing the bleak beauty of Montana (the film was shot in Campion's homeland of New Zealand), and again a prominent soundtrack by Radiohead guitarist Johnny Greenwood ("Oil").

The thunderous and unequivocally most accurate work of his career is delivered here by Cumberbatch. His Phil is carved out of the pain of past mistakes and internalized homophobia. He only realizes the latter when he cries at night or retreats to a secret grove, where carefully concealed magazines with nude athletes and a small lake in which to wash away all the shame and stench await him. An actor who hasn't needed an introduction in the last ten years, who has a huge fan base and a long check from Marvel, consciously takes the biggest risk of his filmography and pays it off handsomely. With the intrusion into his life, Phil Burbank inevitably initiates a tragic transformation, barely staying on the edge of secrecy and revelation (the creaking saddle of that very mentor, the rope woven with special tenderness), quite legitimately cutting off what he hasn't had time to taste - personal freedom. Normally, such transformations are supposed to win a reward or two, but given the dominance of timeless biopics and experimental makeup, we can't hope for anything.

Totally unexpectedly, Cumberbatch's Australian Smith-McPhee also makes an equal appearance. His curious big eyes, his demonic involvement with Phil, his scientific interest in him, and his focus on destruction descend a strong sticky web and bring the matter to a conclusion, while instilling terror in parallel. Dunst, who has finally returned from oblivion to work with serious author(s), also makes a confident and equally tragic second appearance. After working as a cook, her character Rose finds herself in a completely different, rote environment, unable to switch. Jesse Plemons, Dunst's screen and real-life husband, the least prominent member of the cast, manages to fill the space with care and quiet opposition to the tyrant Phil, with whom he has shared a bed and a life for 40 years.

"Power of the Dog" brings out an actual anamnesis of the generationally transmitted image of a man constrained by patriarchal attitudes and the latency of deeply buried feelings. Campion reaffirms and substantiates the finding of the "female gaze" in cinema, its universality, its penetration into areas that some filmmakers do not quite guess at. The only problem, or rather a wish, remains the standard time limit of two hours, which is not always enough to fully feel the overkill and extreme urgency of this cinema. But even in this disciplining time frame, The Power of the Dog manages to both sentence and comfort, and even slightly reassure--in perverse and non-obvious ways from the opposite--its characters with the audience.

File size: 21.5 GB

Trailer The Power of the Dog 4K 2021 Ultra HD 2160p

Latest added movies

Comments on the movie

Add a comment

like

like do not like

do not like